An in-memory supporter once told me that no grief is more painful than the grief you’re living through at the time. But is this true? Is loss really an experience that anyone has the right to rank? Because if it comes down to it, I think few of us can imagine anything worse than the prospect of someone we love taking their own life.

Aside from the visceral realisation of that person’s suffering, there’s affront in the deprivation on our own part – no proper goodbye or due ritual, no chance to intervene and say all the things (or the one thing?) that might have changed the outcome. Yet such unimaginable loss is a reality for many of us. In 2020, 5,224 people in England and Wales took their own lives. Of these, the highest proportion were men aged between 45 and 49 years.

On the eve of National Grief Awareness Week, the culture of remembrance among people left behind by suicide has, at most, a quiet profile in our sector. This needs to change. Within your own supporter base, people in this situation may feel themselves isolated and misunderstood.

This summer, through our in-memory consultancy work, we conducted a series of depth interviews with supporters of Samaritans, all of whom had experienced the loss of a loved one by suicide. These were highly emotional conversations with some particularly brave individuals – who would probably be the last to describe themselves as such. I was struck by some key differences, not just in the way they described their experience, but in how loss of this particular type had affected their needs from the charity, and – in turn – their feelings towards different in-memory offers and services.

An over-riding impression was of the complexity of grief where suicide had occurred. While we talk about the mixed, even conflicting emotions evoked by any case of tragic bereavement (including through sudden illness or accident) – with suicide, such warring extremes appeared far more dominant. Undercurrents of anger, disbelief and regret had made the memorial service intensely stressful for close family, at the same time desperate to remember their loved one well.

There was no sign that the stigma attached to suicide could be left at the door on these occasions. So while some family members had wanted to shout their loved one’s name from the rooftops in loving defiance, others felt compelled (by shame, embarrassment, disbelief) to restrict remembrance to its most private, stripped back form. And yet….

The impulse to take urgent action to help others appeared exceptionally high after an experience of suicide. Samaritans’ Supporter Services team regularly receive calls from people the day after a bereavement has occurred. Some people recoil from the idea of including their loved one’s name on a public memorial. But often, the same supporters are strongly motivated to make a public-facing statement about the need for Samaritans’ services, to be there for others. We coined the idea of ‘privately public’ memorials – ‘quietly special’ to those left behind; but, if they could have a role in raising public awareness about suicide, so much the better[i]. As one fundraiser put it, “We need to channel people’s energies in a way that helps them as much as it helps Samaritans – by feeling like they’ve made a difference to someone else’s life”.

Supporters bereaved by suicide had all experienced (and were still experiencing) trauma. Their need for listening support was painfully acute, especially where stigma had made conversations with family members next to impossible. And empathy (rather than sympathy) made all the difference. Many had found comfort in collective experience, coming together with strangers who ‘understood’ how it felt to lose someone in this way.

For the charity Mind, these findings closely reflect conversations with their own tribute fund-holders, who also include a high proportion of people directly affected by suicide. Through research interviews conducted last year, Mind discovered that the opportunity for supporters to ‘control the narrative’ of their loved one’s memory can be a powerful driver of tribute funds.

Catriona Brickel, Mind’s in-memory fundraiser, shared that, “In the aftermath of a suicide, rumours can fly; and the family may find themselves inundated with both well-wishes and questions. Our supporters appreciated that their tribute fund had offered them a space to write down exactly what they’d wanted to say. They’d preferred sharing details of how their loved one had died there, rather than on social media platforms. Because tribute funds are easily shareable, they could simply direct people to their loved one’s page, saving themselves from difficult conversations.”

Other Mind supporters had appreciated digital forms of remembrance simply for their role in helping build a fuller picture of how well loved that person had been and how much joy they’d brought others. For friends of the loved one who’d moved away, or perhaps just never been in close proximity with the immediate family, the tribute fund had enabled them to share their own personal memories with the family.

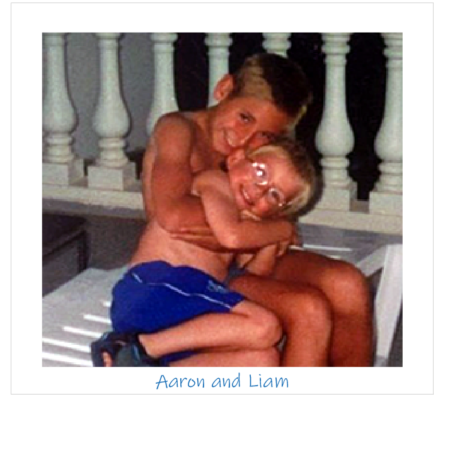

Aaron Hearne, tribute fundraiser extraordinaire, has raised over £255k for ChildLine in memory of his little brother Liam, who died by suicide in 2010 aged just 14. Aaron has spoken and blogged extensively on his experience of losing Liam. For Aaron, the realisation struck at his lowest point that “this was not how it was supposed to be. Liam, the loving person he was, and his memory, were worth so much more than the pain of the last decision he had made”.

Aaron’s subsequent in-memory fundraising journey turned a corner when he could feel people’s focus on his brother shifting. No longer a figure of tragedy, Liam had become associated with the family’s in-memory fundraising effort and the incredible work it had made possible.

If there’s been a heartening outcome from all this research, it’s affirmation that the licence to remember a loved one in a positive way actively helps people in their grief, whatever the circumstances of the death.

What is in-memory fundraising, after all, if not simply bringing to the forefront the aspects of an individual and their life that deserve to be remembered and celebrated? In Aaron Hearne’s words, “I want Liam to be remembered and appreciated for the whole person he was, not just for how he left”.

With thanks to:

- Elaine Cowen, researcher

- Lucy Lowthian, Sheila McGuinness and the team at Samaritans

- Catriona Brickel and the team at Mind

- Aaron Hearne, https://www.theliamcharity.org.uk/

[i] Samaritans publishes downloadable Media Guidelines offering practical advice and tips on how to safely cover the topic of suicide in the media. These include advice on remembering people who have died by suicide in a safe way that doesn’t put other vulnerable people at risk.

To learn more about In-Memory Insight click here.